Feature

Sake Sensei’s Brewery Adventures

Sake production requires access to a bountiful supply of fresh, pure water. Simply turning on the tap won’t do, not to mention the utility bill would be eye-watering. Since sake is made up of more than 80% of the stuff, the quality of the water used makes a huge difference to the quality of sake that can be produced. It’s for this reason that you tend to find sake breweries in close proximity to water sources that have historically proven to be a perfect match for sake production, such as the Nada region of Hyogo, or Fushimi in Kyoto. Even today, Hyogo has the most breweries and produces more sake than any other region in Japan, thanks to the ubiquity of natural water filtering down from Mt. Rokko. Most breweries will access the water source directly from wells or natural springs, but others may source it from rivers or lakes. It is the unique mineral properties of each region’s water that allows for such a diverse variety of sake to be discovered across Japan.

Water is used in copious amounts at nearly every stage of the process, but none more so than during the washing and steeping procedures before the rice is even steamed, as we witnessed firsthand during our visit to Joyo Shuzo (see opposite). Bags of freshly milled rice are emptied one by one into a steel drum, then washed meticulously by hand, in a precisely timed production line of lifting, washing, pouring, rinsing, and repeating, orchestrated under the watchful eye of the toji master brewer, counting out loud during every step. It’s mesmerizing to watch.

More water is required to steam the rice, to be added to the fermenting moromi mash, and finally at the end of the process, to dilute the finished brew and reduce its alcoholic content. Sake will contain about 19–20% alcohol per volume in its natural state, but to really release the flavors, it is usually diluted to something in the 15–16% range. When all is said and done, the amount of water required to produce each bottle is something like 30 times the weight of rice used. Astonishing. Without a source of pure water, you simply cannot make sake.

Kansai Kura Closeup

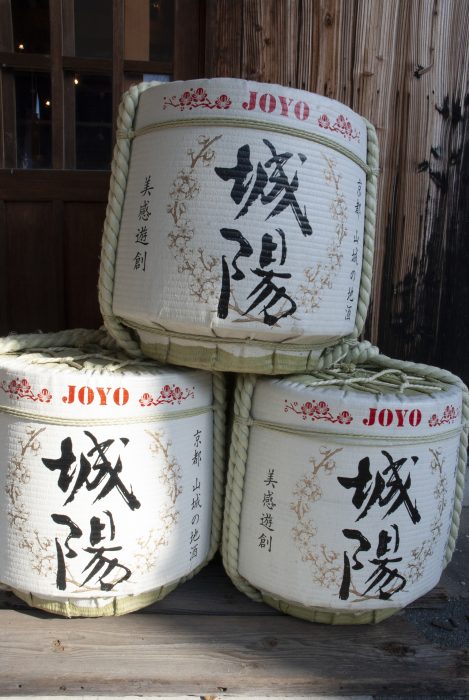

Joyo Shuzo 城陽酒造

Yamashiro-Aodani, an area south of Kyoto near Uji, is more commonly known as a tea growing region (see our feature on p.10) and for its Aodani plum groves. Yet, since 1895, Joyo Shuzo has been brewing sake and umeshu (plum wine) to great acclaim from its location close to the river Kizugawa, whose groundwater provides its vital supply of pure shikomimizu brewing water, drawn from a 100m-deep well.

Its sake has proven popular internationally too, recently picking up a platinum medal for its Joyo Honjozo 65 Ookarakuchi brew at the 2018 Sake Selection held annually in Belgium, and a silver award at the International Wine Challenge 2018 for its Tokubetsu Junmai 60 (2017).

While sake production keeps them busy during the cold winter months, come early summer when the neighboring Aodani plum groves are ripe with fruit, umeshu wine production takes over. Their flagship Umeshu Genshu is almost whiskey-like in its complexity with a deep refined flavor, unlike most overly sugary variations on the market.

With a small team and traditional techniques, Joyo Shuzo maintains a real hands-on approach to its sake brewing. The combination of pure water, dedication to their craft, and their commitment to using only the finest local sake-rice varieties has enabled them to produce a range of small-batch, hand-crafted sake to rival any in Japan.

Address: Kubono-34-1 Nashima, Joyo-shi, Kyoto-fu 610-0116

Tel: 0774-52-0003

joyo-shuzo.co.jp

Their busy on-site store is a testament to their craft. People visit from all over Kansai to taste their latest releases or to buy souvenirs for friends and family.

On Sunday, March 10th from 10am to 3pm they will be holding their annual open house Kurabiraki event where you can sample their sake range, including some limited-edition brews, and enjoy some locally produced food.

Sensei Selection

1. Joyo Ginjo Okarakuchi

吟醸酒 城陽 吟醸大辛口

Using only Kyoto’s premium Iwai rice, this well-balanced dry sake has delicate apple undertones.

2. Junmai Sannen Jukusei Koshu Hesomagari

純米三年熟成古酒 へそまがり

This three-year aged sake is a complex beast of intense flavors with a dry palate.

3. Joyo Junmai Daiginjo — Yamada Nishiki

純米大吟醸 城陽(山田錦)

Using 100% Yamada Nishiki rice grown in Hyogo, this premium sake has a wonderfully fruity aroma with hints of peach.

4. Genshu Tarekuchishu

原酒 たれくち酒

A delightfully crisp {genshu} (undiluted) sake. Best enjoyed chilled or on the rocks.

5. Genshu Nigorizake

原酒 にごり酒

Unfiltered so that you can really savor the taste of the sweet moromi mash. As if you were drinking the rice itself.

SAKE SENSEI

Rakudo Yoshida is Chairman of the Japan Sake Society and has devoted the past 41 years of his life to supporting—and enjoying—Japanese sake, its brewers and associations. He also happens to be a certified laughter therapist.