Feature

Japan on drugs

You might think that Japan does not have much of a drug problem compared to other industrialized countries. And indeed, the official numbers paint a comforting picture. However, as so often is the case in Japan, the truth is hidden somewhere beneath the surface.

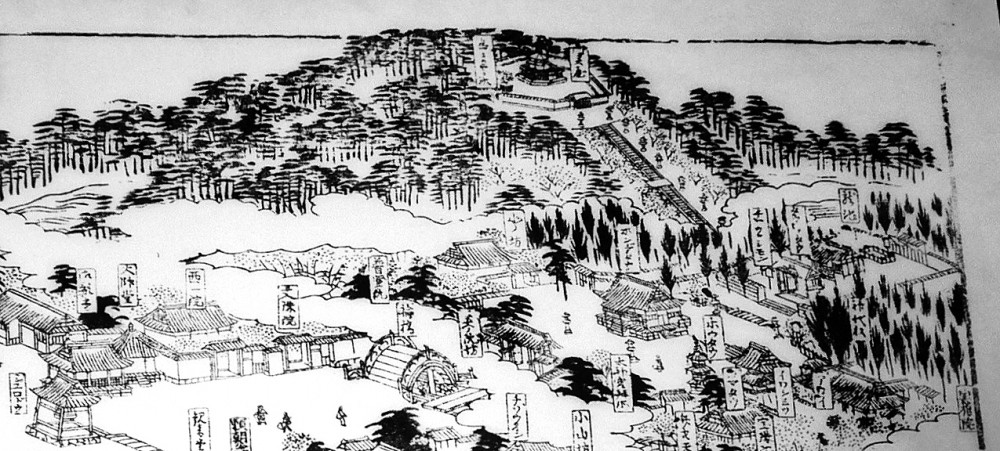

History

Zero tolerance would be the best way to describe Japan’s attitude towards drugs, but it was not always the case. The Japanese drug of choice is kakuseizai. Commonly translated into English as ‘stimulant’ it is a collective name for all ‘upper’ drugs and mostly refers to amphetamines or speed. To understand the problem we should first take a look at the history of the drug and its relationship to this country.

It was in 1893 that Japanese chemist Nagayoshi Nagai created a new chemical combination from ephedrine which would become known throughout the world as amphetamine. In the lead-up to the war the powerful stimulating effect of amphetamine was recognized by the state-backed company Dainippon Pharmaceuticals (current day: Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma) and it was brought to the market as a prescription drug under the registered trademark Philopon as a drug to treat a variety of ailments such as narcolepsy, alcoholism and Parkinson’s disease. Amphetamines boost concentration and energy and they are still used today in prescription drugs like Adderall prescribed for ADD, even to children. Though official sources deny it, independent sources have confirmed that during the second world war the military gave the drug to pilots and soldiers. This explanation would account for the overproduction of Philopon at the end of the war, when the drug flooded the market and its use was widespread among all layers of society in the distraught post-war period. This led to quite an epidemic and by 1950 the government stepped in with new laws, listing amphetamines as a narcotic and banning production and sales. The country was already hooked on the highly addictive uppers and the drug took to illegal production labs and black markets. The trademark name Philopon was banned too and the drug continued in illegality under the slang name shabu. The ban in combination with efforts by the police was successful

in rooting out most of the illegal production in Japan itself, but then the post-war economic boom made the country attractive for international smugglers. This saw theintro- duction of a diverse array of drugs including cocaine, LSD and cannabis as well.

Current

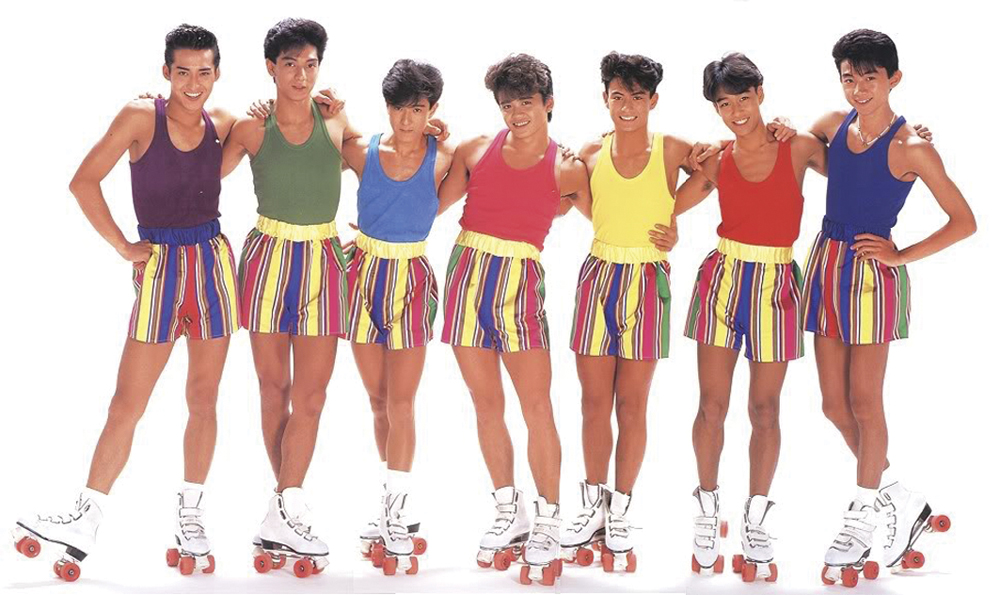

Today amphetamines are still the biggest problem. You hardly ever hear about it on the news, except for when a foreign dealer is arrested or a celebrity is caught using drugs. Such was the case in the summer of 2009 when the arrest of pop idol Noriko Sakai was dragged out over the news for many weeks. This really showcased the cultural stigma attached to drug use in Japanese society. Regardless of the minuscule amounts of amphetamine that were found and the overall weak case the Tokyo police had against her, within days her record label and sponsors dropped her, and her clothing line and albums were pulled from stores. A stark contrast from the apparent ease with which Hollywood actors and international pop stars stroll in and out of some of the world’s more expensive rehab clinics.

Popular as ‘upper’ drugs are in Japanese fast-paced society, the relaxant cannabis is equally liked. Despite being less potent, under the law here cannabis is regarded the same as any other drug, even if it grows naturally on the northern island of Hokkaido. Use of the drug had never been widespread until after the adoption of the American based anti-drug laws in the 1950s. The US has since seen some gradual loosening in their anti cannabis stance, with medicinal cannabis now being legalized in several states and the recent announcement by New York City mayor Bloomberg to decriminalize possession for personal use in the city. The Japanese law still resembles the tough stance on cannabis taken by the US in the 1930s. In Japan, the drug is popular among young people. Satoshi, a 28-year old company worker from Osaka says, “I smoke it with friends when we go on surfing trips. I sometimes buy it from my friends, I don’t know where they get it from.” To bypass the law in Japan and in other countries recent years have turned up a substance known here as goho haabu or dappou haabu. (‘legal herbs’ or ‘law-evading herbs’.) Basically it is a synthetic cannabis. It’s a combination of natural herbs treated with synthetic cannabinoids, the active substance in cannabis. Stores selling this, for now, legal substance have popped up in major cities throughout Japan in no time. Satoshi tells me, “There are many incidents with this stuff, you hear about people getting in trouble with the law on the news every day. Also because it is chemical you don’t know what exactly is in it. This is anecdotal, but I heard a friend of a friend that smoked it a lot developed a speech impediment.” Officially the herb is meant to be burned as incense and will have a relaxing effect on anyone in the room, however if you smoke and inhale it directly the effect is like a strong weed or hash. Statistics from the Japanese government on cannabis use indicate a far smaller number of users then amphetamines, but these numbers are based on court convictions. A 2009 study by the US Department of State on international narcotics control strategy stated that “cannabis use is widespread in Japan.”

Battling addiction

Another thing that adds to the problem is the way drug users are dealt with. Hardcore addicts are often placed in mental asylums where there is little or no addiction treatment. Most of these ‘patients’ are long-time speed users. These patients can be kept in the asylums indefinitely and are often sedated, creating a new problem and a new addiction without ever looking at the initial addiction problem or its cause. Those of sound mind and body who are caught selling or repeatedly using drugs are sentenced to prison with hard labor in Japan’s disciplined, military-like penal system. First-time offenders who possess small quantities of cannabis deemed for personal use might get off with a suspended sentence. Meaning if you slip up in any way for a period of several years set by a judge you will go to jail. The minimum amount to constitute a drug offence is extremely low and there have been cases where people were prosecuted for possessing as little as 0.01 grams. In prisons, like in the mental asylums, there is little room for rehabilitation programs, which in combination with the addictiveness of speed in particular makes sure that drug offenders have the highest recidivist rate among the Japanese prison population.

In the early 90s, western-style rehab meetings were set up in a small Tokyo café by a reformed alcoholic and speed user turned catholic priest, Father Roy Assenheimer, and former speed addict Tsuneo Kondo. Modeled after the faith-based Alcoholics Anonymous program, this was the first introduction in Japan of a program aiming to battle addiction problems, rather than battling the crime problem. This grew into a national organization with more than 60 chapters all over Japan called Nihon DARC (Drug Addiction Rehabilitation Center), which is still headed by Mr. Kondo today.