Feature

The Colorful World of Kimono

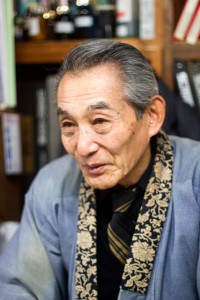

“Color is Eternal” – Inside the vanishing world of yuzen kimono with master textile artist Kihachi Tabata.

Beautiful, mysterious, and iconic: For many Japanese, the kimono is not just a fashion statement but a bridge to the past, with many passed down and re-cut from one generation to the next. As the hub of tradition and art in Japan, Kyoto remains the beating heart of kimono fabrics, with a myriad of styles and methods in use to this day. To learn more, I met Tabata Kihachi, one of the best known kimono dyers alive today, and a regular supplier to the local geisha community.

Beautiful, mysterious, and iconic: For many Japanese, the kimono is not just a fashion statement but a bridge to the past, with many passed down and re-cut from one generation to the next. As the hub of tradition and art in Japan, Kyoto remains the beating heart of kimono fabrics, with a myriad of styles and methods in use to this day. To learn more, I met Tabata Kihachi, one of the best known kimono dyers alive today, and a regular supplier to the local geisha community.

The fifth in a line of master craftsmen, Tabata took the name “Kihachi” as part of the legacy he inherited. His grandfather, the third Kihachi, was designated a Living National Treasure by the government. Despite this, he insists that his continuation of the family legacy was far from inevitable.

“It’s true I was the elder brother, but my father never said anything about it. When I graduated from high school there were several things I could have done, actually at that time I didn’t much like Kyoto. My father was famous and we were a rich family. There was always a fuss whenever I went somewhere – ‘Where are you going?’ ‘When are you coming back?’” he said.

When he graduated high school, he had different ideas than his parents about what his next step would be. “My parents wanted me to go to Kyoto University, but I wasn’t impressed by the kind of education there. In the end I decided to go to Waseda, where I could study art practically, not as a scholar,” he explained. It wasn’t until he returned to Kyoto to complete his postgraduate that he chose to join the family tradition.

Originating in the Edo period, the yuzen style of dyeing kimono employs a rice-gluten resist, painstakingly applied to inked outlines to act as a barrier to the dye. This is the key to the highly intricate patterns that define the craft. As dye is applied, color emerges in a series of layers.

“It’s like a romance,” Tabata beams. “When you first meet a woman, she might not be wearing much makeup, but if she likes you, then next time she might wear a bit more. She reveals herself this way, and then at the wedding her face is beautifully decorated.”

Coloring can be done by hand (tegaki yuzen) or in sets through special stencils made of paper washed in persimmon-juice (kata yuzen). After the dye is applied, the fabric is steamed, washed and dried, and the color sealed in place with a second layer of gluten.

“Color is eternal,” he says flicking through a series of oversized scrapbooks that he calls the treasure of his family. The pages are lined with cuttings of silk in a beautiful array of hues and weaves. “Even though you might look at something and say ‘this is red,’ it’s ultimately something relative to the person. That’s why it’s important not to be abstract but to have the specific color.”

“Color is eternal,” he says flicking through a series of oversized scrapbooks that he calls the treasure of his family. The pages are lined with cuttings of silk in a beautiful array of hues and weaves. “Even though you might look at something and say ‘this is red,’ it’s ultimately something relative to the person. That’s why it’s important not to be abstract but to have the specific color.”

As for the colors Tabata likes the best: “Indigo is especially versatile. It’s the most natural color – the color of the sky and ocean – and it matches anyone.”

Like many Japanese master craftsmen, Tabata can be a bit reticent about what makes his own work unique. When I ask how a collector or other expert might recognize his work, he waves a hand dismissively. “Oh, just the appearance – you’ll see my work from the appearance of the whole, not a specific thing,” adding that until his father’s generation, the Tabata name was well known for a palette of five colors, particularly green and vermillion, but that he himself chose not to continue this tradition.

With kimono tending to hide the natural contours of the body, the seduction is in the details. “Look at the inner lining of the sleeve,” he says gesturing to a beautifully patterned white-and-indigo kimono, which took a full year to complete. “Everything is hidden – even showing the legs is taboo … But allowing a glimpse of more vivid color inside the sleeve – this kind of detail used to be very fashionable – and expensive.”

Tabata describes himself as more helper than master, someone whose job is to help women “blossom” and find beauty in themselves. “When I see a beautiful woman wearing my kimono, I think, ‘I did it, baby!’ I have to try to understand women – but who can do that? Can you?” he chuckles.

As for keeping up to date with fashion trends, he said “Sometimes I’ll check the department stores and see what color lipstick women are wearing. I try to be ‘half a step’ ahead of the customer.”

He uses the expression shinra bansho to describe the source of his inspiration. Virtually untranslatable, it describes the limitlessness of phenomena. “Nature, personality… and when I change something it comes back to this feeling. Everything has to be studied more; shapes, colors – you have to put all of your soul into it.”

Where sellers like Takashimaya used to boast of their kimono being “100% made in Japan,” today the vast majority of silk is imported from China and Brazil, and only a handful of factories in Gunma and Yamagata prefectures continue to spin raw silk. With the rise of machine-made fabrics, the number of yuzen artists has dwindled to a handful, and of these, fewer still have succeeded in passing on their craft to a successor.

“It’s really hard,” explained Tabata, “Hardly anyone can inherit my way of thinking – it’s almost impossible. Just studying is not enough – it has to include everything. Even the simple basics of a person’s life are so different – westernized – ways of sitting, working, eating… houses and apartments are different. But even young people have a sense of what we call kaiki genshou (returning to one’s origins). The craft will continue somehow.”

Geisha gazing

April is by far the best month to catch a glimpse of real maiko (apprentice geisha) in traditional dress, with a busy schedule of festivals and public appearances. You might even see one of Tabata’s creations!

Prices vary by seating, usually with multiple performances throughout the day.

Miyako Odori– biggest and most spectacular performance by geisha of the Gion Kobu district, held daily in April. Location: Gion Kobu Kaburen-jo Theater |

Kyo-Odori– second-biggest dance, by the Miyagawa-Cho district, held daily from the first through to the third Sunday of April. Location: Miyagawa-cho Kaburen-jo Theater |

Kitano Odori– fine performance in a more intimate setting by geisha from the Kamishichiken district, held daily from April 15–25 Location: Kamishichiken Kaburenjo Theatre |

Kamogawa Odori– also excellent, with geisha from the Pontocho area, held daily from May 1–24 Location: Ponto-cho Kaburen-jo Theater |

染織の芸術

「色彩は永遠」と語る染織家の田畑喜八さんが、失われゆく京友禅の世界をご案内

美しく、神秘的で、象徴的。日本人にとって着物はただのファッションではなく、過去と現在をつなぐ橋のような存在だ。先祖代々受け継がれる着物もあれば、親世代の着物を別の用途に仕立てなおすこともある。伝統工芸の中心地である京都は、今でも着物の生産が盛んであり、無数のスタイルや手法が受け継がれている。この世界をより深く学ぼうと、現代日本でもっとも著名な染織家の一人である田畑喜八さんにお話をうかがった。田端さんは、地元の芸姑さんたちの着物も数多く手がけている。

京友禅の名跡である田畑喜八の五代目を襲名し、祖父の第三代田畑喜八は日本政府より人間国宝の指定を受けた名人。それでも当代の田畑喜八さんは、家業の継承を強制されたことがなかったと明言する。

「確かに私は長男ですが、父から家業について言われたことはありません。高校卒業後の進路はいくつか考えていました。実を言うと、当時は京都があまり好きじゃなかったんです。父は有名人だし、名のある家だし、どこへ出かけるのにも一悶着ありましたね。どこへ行くんだ、帰りは何時だって」

高校を卒業するときに、田畑さんは親の思惑と異なる道を選ぶことにした。

「両親は京都大学に行かせたがっていましたが、京大で学ぶことに興味はなかった。結局は早稲田大学に行きました。学者を目指すのではなく、そこで実践的に美術を学ぼうと決めたんです」

そして大学生活を終えて京都に帰り、田畑さんはようやく家業を継ぐ決心をしたのである。

江戸時代に起源がある友禅の染織は、米のでんぷん質からなる防染剤で繊細な輪郭線を布に描く。これが複雑な模様を染め上げるのに不可欠な工程で、重層的な色調を浮かび上がらせる秘密なのである。

江戸時代に起源がある友禅の染織は、米のでんぷん質からなる防染剤で繊細な輪郭線を布に描く。これが複雑な模様を染め上げるのに不可欠な工程で、重層的な色調を浮かび上がらせる秘密なのである。

「男女の間のようなものですよ。最初に会ったときには化粧気もなかった女性が、相手に気があれば次に会うときは少しおめかしをしてくる。女性はこうやって次第に自分の気持ちを明かしていって、結婚式では本当に美しい化粧を纏っているというわけです」

本格的な手描き友禅もあれば、柿渋紙の型紙を用いる型友禅もある。色挿しが終わると蒸して色を定着させ、友禅流しで洗ってから乾燥させる。そしてさらにその上から、第二の色彩が防染剤とともに染め付けられていく。

家宝であるという何冊もの大きなスクラップブックをめくりながら、「色というものは永遠です」と田畑さんは言う。線が引かれた各ページには、さまざまな美しい色調の端切れが集められている。

「色を見た人が『赤』と言っても、色は見る人ごとにまったく違う。だからこそ抽象的な名前ではなく、それぞれの色に固有の名を付ける必要があるんです」

好みの色を訊ねると、田畑さんはこう答えた。

「万能なのは藍ですね。空や海の色でもあり、誰にでも似合ういちばん自然な色です」

日本の多くの職人がそうであるように、田畑さんも自分自身の作品を語るときは謙虚だ。コレクターや他の染織家が、一目で田畑喜八の作品だとわかるような特徴はどこかと訊ねると、手を振りながら素っ気なく答えた。

「ただの見かけですよ。細かい要素じゃなくて、全体的な色や形でわかるのでは。父の代までは、田畑喜八といえば緑色や朱色などを含む五色が有名だったのですが、私はその伝統を引き継がないことにしたんです」

体型を隠す衣類もである着物は、その魅力を秘めやかな細部に宿している。完成までに丸一年かかったという白地に藍色の美しい文様を見せながら、田畑さんは説明する。

「この袖の裏地を見てください。脚を見せるのもタブーですから、こういうのはすべて隠された意匠です。でも袖の内側に鮮やかな色がちらりと見えるようなデザインは、とてもお洒落で贅沢なものだとみなされてきました」

表現者というよりは、脇役であると自認する田畑さん。女性の内なる美しさを咲き誇らせるための手助けが、染織家としての役割なのだという。

表現者というよりは、脇役であると自認する田畑さん。女性の内なる美しさを咲き誇らせるための手助けが、染織家としての役割なのだという。

「私の着物を着た美しい女性を見たときは、やった!と思いますよ。女性のことをもっと理解するために努力しなければ。でもそれが難しいんです。あなたはできますか?」

そう言いながら田畑さんは笑った。

また田畑さんは、現代のファッショントレンドを研究する努力も怠っていない。

「ときどきデパートに行って、女性がどんな色の口紅をつけているのかを確認しています。お客様より半歩先を行けるように努めています」

インスピレーションの源泉を訊ねると、それは森羅万象だという。この世界にある無限の存在が染織の題材になる。

「自然も、人柄も、すべてです。何かを変えるときには、この気持に立ち帰ってくるようにしています。形も、色も、あらゆることをもっと学んで、全身全霊で仕事に打ち込まなければなりません」

高島屋などで100%日本製を誇っていた着物も、今では絹の多くを中国やブラジルからの輸入品に頼るようになった。生糸の生産を続けているのは、群馬県と山形県にあるいくつかの工場のみ。機械織りの隆盛によって友禅の染織家は激減し、その中でも次世代に首尾よく伝統技法を継承できている者はさらに少ない。

「本当に難しい問題です。私の考え方を受け継いでくれる人はほぼ皆無で、継承はほとんど不可能かもしれません。友禅はただ技術を学ぶだけでなく、すべての要素が必要です。基本的な生活様式も西洋化されて、大きく変わってしまいました。座り方、働き方、食べ方、家やアパートなども昔とは違います。でも若い人に回帰現象のようなものを感じることもありますよ。伝統は何とか受け継がれていくでしょう」