Art

Don’t Blink! The fleeting world of Japanese woodblock prints

Who has not seen it? Who has not felt the massive lift of salt-streaked, indigo wave stretching patently abstract fingers of foam at its crest, poised to overwhelm the distant, snow topped Mount Fuji? Who has not sensed the trepidation of the fishermen closely huddled in their boats, sluicing down the opposite slope into the trough of this great mass of water? Recognizable the world over, Hokusai’s The Great Wave Off Kanagawa is an iconic example of the ukiyo-e genre of Japanese art. It is prophetic as well, because such intricate and evocative landscapes, incorporating influences from the Western art world, would constitute the last phase in a centuries-long development.

Move forward a few seconds from that captured moment and the wave will collapse. We cannot know the fishermen’s fate, but skip ahead a few decades and the ukiyo-e woodblock print tradition itself will collapse along with the industry that supported it, employing image designers like Hokusai, wood block carvers who produced up to a dozen blocks for a single image (one for each color), and the publishers who turned the wheel of profit that had kept the business afloat.

For many years in Osaka’s Dotonbori district, when it was home to five kabuki theaters, Takano Seiko, the curator of the Kamigata Ukiyo-e Museum, was proprietor of an all-night café. “The actors used to walk through this neighborhood,” she told me. “But gradually the theaters closed and the actors disappeared.”

I have come to Takano-san’s museum to find out more about the origins of ukiyo-e and how the art form developed in the Kamigata region, as the Kansai area was once called. To understand ukiyo-e, we must first get to grips with the etymology of Ukiyo: The Floating World. The Japanese verb uku means “to float,” but as with many Japanese words, its boundaries of nuance go beyond that of the English translation. Uku can suggest an emotion quickly passing over a person’s face; extravagance; a smile or frown playing at the lips; to be carried away by frivolous passion or even to feel blue. Combined with yo, meaning “world,” ukiyo-e encapsulates Japan emerging from an age of civil war into one of peace and, for the common folk, a prosperity theretofore unknown. It was also a time of lurking disaster. Fires and earthquakes repeatedly ravaged even Edo, the capital city we now know as Tokyo. One could, without warning, become bereft of property and family overnight. And so from the gold and the ashes a spirit of living for the moment prevailed: knowing one’s life to be transient as the perfection of a spring cherry blossom. The epicenters of this culture were the places of diversion: theaters, sumo stadiums, and pleasure quarters. These were the places where ukiyo-e, “pictures of the Floating World” first appeared.

The Floating World’s core was Edo, but its lifestyle found havens in the western cities of Osaka and Kyoto. In the 1700s Edo’s first ukiyo-e were monochrome portraits advertising actors, wrestlers, and courtesans. At the same time in Kamigata, ukiyo-e was more of a cottage industry, with fans or clubs producing woodblock printed books or hand-painted portraits of celebrities. In Edo the advertising fliers quickly evolved into souvenirs. Prints became more elaborate. Color was added, at first by hand-painting the finished prints, as were background embellishments, such as seasonal flowers. Then the technique of printing large, multicolor editions, using only woodblocks, made them even more affordable. In Kamigata, it was not until the 1800s that single-page prints became popular.

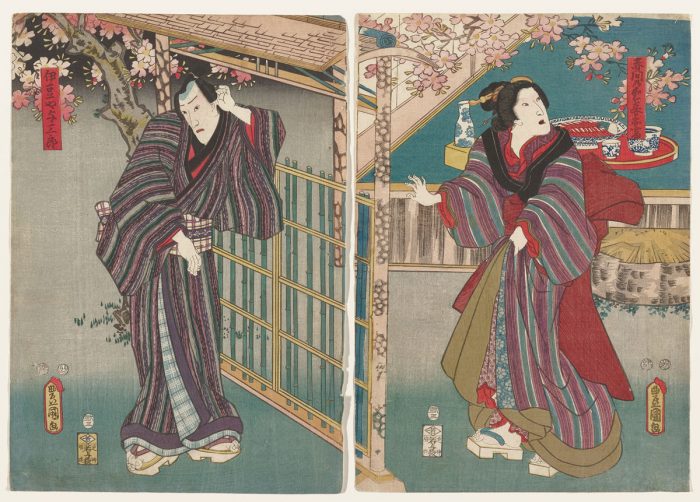

By the nineteenth century, patrons in both east and west Japan could buy realistic and dynamic reproductions of pivotal scenes in kabuki performances to display in their homes, but the styles differed between the regions. In Edo the focus was on the elegance of the characters, smoothing over the personal appearances of the performers, especially where the subjects were men playing female roles. In Kamigata it was the actor’s own character and features that were faithfully rendered and a print sometimes included calligraphy or poems in the actor’s own hand.

“The footsteps of the kabuki actors have faded,” Ms. Takano says, “but people can still follow them. Displaying these pictures brings happiness to the actors’ spirits and to the people visiting this neighborhood in the present.” Ms. Takano amassed a collection of Kamigata ukiyo-e so large that she herself no longer knows its number. In 2001 she demolished her café and on the same site built the Osaka Kamigata Ukiyo-e Museum. The space is small and can only display about 30 prints at one time. The theme of the spring exhibition is, of course, the evanescent cherry blossom.

While some time has passed since ukiyo-e’s demise, it is no surprise why the art has found devoted fans in the likes of Ms. Takano today. Inspired by the ephemeral, they give longevity to its expressions. So let your feet take you where you can enjoy them with your eyes instead of your imagination.

Kamigata Ukiyo-e Museum

Address: 1-6-4 Namba, Chuo Ward, Osaka

Hours: Tues-Sun 11am-6pm

Website: kamigata.jp/kmgt/jp/english/